|

|

#51

|

|||

|

|||

|

uh and "KG 200 - The True Story" by Peter Stahl

|

|

#52

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

Quote:

The biggest problem with his books is the fact that the typist doesn't understand engine power settings and therefore incorrectly converts between psi boost and ata throughout the text, littering it with parenthetical errors which were obviously absent from the original manuscript. Quote:

Quote:

Quote:

I don't recall as much interest in tactical Mach numbers as was displayed by the Allies, because in the late war period the Germans often found themselves climbing into battle, whilst the Allied escort fighters were diving from on-high. Quote:

|

|

#53

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

Quote:

Quote:

Quote:

The thing that you point about the Ta-152 happened with other planes as well: the incorrect use (or lack) of fuels meant that they were more general handling tests instead of performance ones. Quote:

http://www.unrealaircraft.com/hybrid/spitfire.php Quote:

|

|

#54

|

||||

|

||||

|

Quote:

The main advantage of Brown's test results is that they are internally consistent; it's the same guy flying all the aeroplanes, so you get a real comparison between aeroplanes rather than a comparison between pilots. This is especially important when you come to consider handling, since it was strength limited in large parts of the envelope, particularly at high speed. His tests of German aeroplanes are especially good because of course his German was good enough that he understood the captions in the cockpit, could interrogate pilots & ground crew, read manuals if available etc.. This means that there's considerably less risk of under-performance due to poor technique than might otherwise be the case. Quote:

Quote:

The lack of MW50 & GM1 doesn't necessarily fatally compromise the Ta-152 tests, since you can calculate the additional power which they would have provided and hence deduce what the maximum performance would have been. Of course, to do this properly you need to have enough other test data to infer the shape of the drag polar, but you only really need this information for a relatively narrow range of CL. It's really amazing how much you can deduce about aircraft performance from quite limited data. In fact, some people make careers of it. For example, one of the main reasons for scrupulously fitting exhaust nozzle blanks to shiny new fighter jets when they're in the static park at an airshow is that if I know the nozzle throat area then an experienced observer estimate the engine thrust with rather better accuracy than the layman might expect. In any case, the handling is generally more interesting than the kinematic performance, since it's far easier to calculate kinematic performance than it is to calculate handling characteristics, especially at transonic speeds. [QUOTE=Sternjaeger II;281235]apparently it was just a genuine performance test to see whether they could improve the handling of their 109s, have a look at this interesting article http://www.unrealaircraft.com/hybrid/spitfire.php I think I might have come across this before at some point. The comparison argument is a strange one, because firstly it's irrelevant to combat, and secondly no two installations are alike in any case. Since the Germans weren't stupid, my best guess is that:

In the latter instance, this would imply that they were yet to capture a flyable Mark IX or XII. It's worth noting that the RAE, with access to high grade fuels, took the former route with their early captured Fw190s, handily exceeding rated boost (and possibly rpm, though I'd have to check my copy of Wings of the Luftwaffe). I suppose this might technically be called the fly it like you stole it approach... Quote:

However, it's important to remember that the Germans were under no obligation to (for example) use the same standard atmosphere assumptions as us, or to test their aeroplanes according to the same methodology. So if you want to make a really satisfactory comparison it's not sufficient to just perform a unit conversion and overlay the data; you've got to actually drill down to find out what the assumptions underlying the test results were, and then correct everything to a common standard. Otherwise it's apples vs oranges. I think I went into this in my flight testing thread. Hopefully in a few patches time, when things are sufficiently stable for serious testing, we will have amassed enough of this underlying information on assumptions to allow everything to be converted to modern ISO standard conditions so that fair comparisons can be made. However, since I don't have a great deal of German data on test methodologies, German standard atmospheres and so on, I'm very much reliant upon the wider community to fill in the gaps. |

|

#55

|

|||

|

|||

|

Ta 152, Spit Pr XII, Komet ... Where are our sturdy early war planes Hurri and Spit I ???

|

|

#56

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

The tail plane is affected too but this is not the primary prob. In fact it impact the transonic regime by raising the overall drag of the plane as a consequence of the mach shock on the wing itself - e.g : the compressibility - that alrdy affect the plane with a nose down torque. the thiner is the wing (thickness/cord) , the latter does this occur due to overall smaller camber ratio. The easiest solution found at the time was to use symmetrical wing section. Once the wing mach shock wave has been addressed then the tail shock became a problem you are right (take a look to the X1 story) ~S Last edited by TomcatViP; 05-12-2011 at 03:25 PM. |

|

#57

|

|||

|

|||

|

/Off topic

You are correct, and the Bell X-1 stole an idea from the British Miles M-52, an aircraft that Brown was sure would have exceeded Mach 1 and he was slated as the possible pilot for the prototype. The M-52 had an 'all-moving' elevators that cured the problems that Bell had with the shock wave from the wing causing 'washout' of the X-1's elevators and loss of control as you neared Mach 1, a phenomenon that some WW2 pilots (P-38 Lightnings in particular) also experienced in sharp dives. |

|

#58

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

Quote:

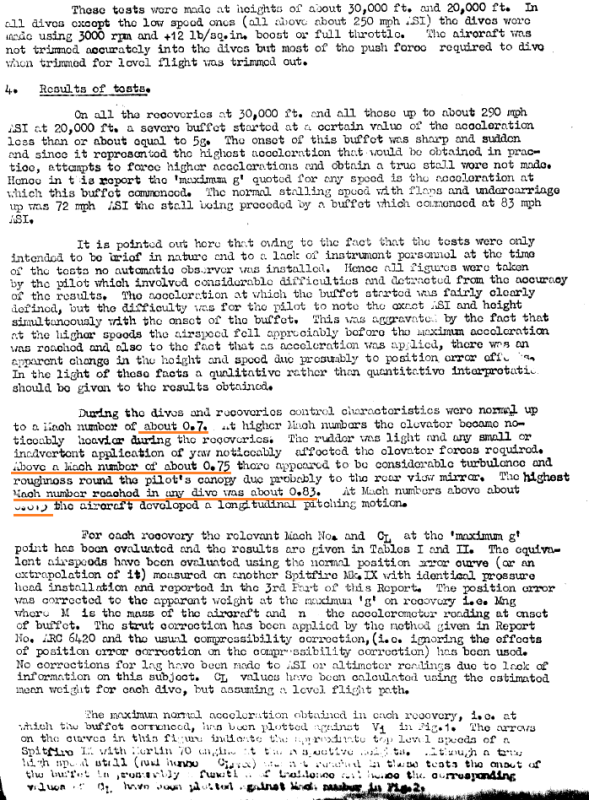

Basically I think the Mach 0.85 dive limit is arbitrary, ad hoc, ex stomach etc. - a bold guesswork that was set well before they would test the actual capability, just like many of the era's limits, though a bit bolder.. But, personally I believe the behaviour shown by fighter Mark IX BS 310 was certainly no greatly different - better or worse - than just about any WW2 fighter: controls functioned normally up to about .70 Mach, then all sorts of anomalies began to appear.. and at 0.815, there's already a longitudal pitching motion - and 0.85 is still rather far away..

|

|

#59

|

|||

|

|||

|

Just to add affirmative information about what Viper said about the elliptical wing design of the Spit a little albeit interesting information on a footnote in aeronautical warfare history about a plane that didn't make it into mass production but would have produced a mess if it had been mass produced (you'll quickly will see why): the Heinkel He 112 that had been the most serious competitor against the Me109 during the evaluation trials in 1935 but which - as we know - was won by the 109.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/He_112 http://www.aviastar.org/air/germany/he-112.php Although the He 112 did have elliptical wings and wing-to-fuselage transition similar to the Spit its first prototypes had some problems with speed and the designers suspected some extra drag they didn't take into account during the initial design stages. They solved it in the course of pre series development but the contract has already gone to Messerschmitt. So obviously elliptical wings aren't the miracle some come to think. Some nice pics and a short video clip on the 112 used as a testped: http://www.cockpitinstrumente.de/Flu...%20Profil.html Last edited by 41Sqn_Stormcrow; 05-12-2011 at 06:21 PM. |

|

#60

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

Obviously, with manual controls, both of these Mach numbers depend upon pilot strength. Limits in the Pilot's Notes are there to protect the airframe and engine from harm, so they will tend to correlate more closely with what Brown would call the critical Mach number than with what he would call the tactical Mach number. N.B. - This nomenclature is inherently confusing the aerodynamicists, who would tend to think of the critical Mach number as the lowest freestream Mach number at which sonic flow is seen around whatever shape they're examining. Therefore, for example, you can't look up aerofoil critical Mach numbers in Abbot & Doenhoff and compare them with flight test reports. Quote:

Quote:

I'd say that it's probably reasonably safe to place the tactical Mach number of the Spitfire at approximately 0.80, perhaps higher for the Griffon Spitfire due to its longer nose and correspondingly higher fineness ratio. Additionally, comparison with the P-51D is interesting: http://www.wwiiaircraftperformance.o...-divetest.html http://www.wwiiaircraftperformance.o...-27-feb-45.pdf IMO the Spitfire comes out of this comparison looking pretty good. Do you have the rest of this report? It's interesting stuff. Note, however, that it's a somewhat different animal from the PR.XI tests. The PR.XI tests were aimed at getting the highest possible Mach number on the clock. They therefore involved dives from about 40000', the maximum Mach number being reached at about 29000' with the aeroplane unloaded; recoveries were pretty gentle at about 2 g. Meanwhile, your report appears to be an attempt to investigate the effect of Mach number upon CLmax; it talks about 5 g recoveries, which is pretty brave out at the edge of the envelope; the Mustang dive tests emphasise the risk of structural failure unless extremely gentle recoveries are made from high Mach number dives. It's hardly surprising that the maximum Mach number at which you can really throw the aeroplane around would be lower than that which can be reached if gentle flying. I'm actually quite surprised that the Spitfire would tolerate this sort of handling at such high Mach numbers; there's no mention of rivets popping, things bending, breaking or falling off etc. I can't think of any other WWII fighter that would repeatedly tolerate >5 g at M>0.80 without complaint. So I suppose that a lot of this stuff is in the eye of the beholder, but if I had to spend my time at the top right hand corner of the envelope for real in a WWII fighter then I'd pick a Spitfire to do it in. The caveats regarding date collection in the report are important; it's quite hard to work out exactly what the uncertainties are with this sort of test. They might easily be as high as +/- 0.03 M. In this respect the PR.XI data is better because an auto observer was used AFAIK, and of course the aeroplane was quite heavily instrumented and modified in other respects as well. So I'm quite confident that their quoted Mach 0.89 is +- a rather small error (though I don't make any particular claim as to the applicability of this figure to an operational aeroplane on a squadron, beyond the qualitative implication that the basic airframe was selected for dive tests by the high speed flight because it had the best high Mach number characteristics available off the shelf). However, it's important to make the distinction between the uncertainty due to observational difficulties, those due to lack of instrumentation, and those due to instrument errors. For example, if the ambient conditions (especially static temperature) aren't recorded, there might be a considerable error in Mach number due to differences between the test day and standard atmosphere conditions. Not much can be done about this, because even a couple of hours later the weather can and probably will have changed. OTOH, it's much easier to go back a few weeks later and correct for instrument error by careful calibration of the instruments used during the test, and measurement uncertainly can be reduced by repeating the tests and applying statistics. I point this out because there is a tendency for certain sections of the community to suggest that just because some reported dive is considered bogus (usually a combat report for their favourite aeroplane citing 600 mph IAS or something) that all dive testing is bogus. The reality was of course that it was merely difficult to get good data in the 1940s; serious flight test organisations could do it, whereas the average fighter pilot could not, because nobody had seen fit to give him the necessary tools to do so. /// Tomcat et al, conventional elevators work by modifying the camber of the tail section. Moving the relatively small control surface therefore affects the CL of the entire tail. The force required to do this is set by the hinge moment. At high freestream Mach number you get sonic flow over the tail. The control surface cannot affect the pressure distribution over the tail surface upstream of the sonic line. So the control effectiveness suddenly dramatically declines. Since the control deflection was limited by pilot strength, the effect that the pilot perceives is a nose down pitching moment, because he's pulling as hard as he can, and the stick stays in the same place. But what's really happened is that the elevator effectiveness has declined, which is equivalent to reducing the absolute camber of the tail. This means that high Mach number departure was often a 2 stage phenomenon. First the aeroplane starts wanting to pitch down due to shock formation on the wing changing the downwash angle over the tail. Then at some higher Mach number the effectiveness of the elevator fades away and the nose down pitching tendency gets worse. A lot of aeroplanes wouldn't really get into this second regime because they'd either break or start slowing down and getting into warmer air first. Obviously, an all moving tail doesn't have this elevator problem because it just changes alpha rather than translating its lift curve slope with camber changes. It has other problems due to the force required to actuate it, possible overbalance etc. But you can fix most of them by just throwing massive irreversible screwjacks at it, although it is advisable to combine this with Q feel so that the pilot doesn't inadvertently break the aeroplane when flying fast... Yeager suggests that keeping the flying tail secret allowed the F-86 to have a technological lead over British and Russian aeroplanes of the period, but really this is an oversimplification because the idea of the all moving tail was not new. The rather more mundane reality is that getting the enabling technologies in the rest of the control system to work wasn't a trivial problem in the 1940s, and in Britain almost all of the funding for such work evaporated in 1945, whereas in America it kept on flowing. Meanwhile the Russians had slightly different priorities, but it's probably fair to say that the kill ratio achieved by the UN in the Korean war was probably more a function of pilot skill than aircraft performance differences (though the F-86 was superior at high Mach number, it was certainly far from perfect). BTW, the first generation X-1 wasn't as clever as the M.52. AFAIK the M.52 had no elevators and just moved its entire horizontal tail for pitch control "out of the box". The X-1 had elevators for pitch and an all moving tail for trim (rather like a Bf-109, except that the X-1 moved the tail electrically, and the control was a coolie hat on top of the stick). The elevators became ineffective somewhere in the transonic regime (0.9ish) and the workaround was to hold the stick still and control pitch with the trimmer. I assume that the 2nd generation aeroplanes ditched the elevator... Of course, despite its aerodynamic sophistication, it's not entirely certain that the M.52 would actually have been supersonic in level flight as drawn because this would have been asking an awful lot of its engine. But now we're waaaaay OT. Last edited by Viper2000; 05-13-2011 at 01:27 PM. Reason: broken quote tag |

|

|

|