|

|

#171

|

|||

|

|||

|

The Polish airforce have some good pilots, although I can't say much for planes. They flew Spitfires in England but in the begining, they all were like the Soviet I-16 and I-153 in a way, only worse.

|

|

#172

|

||||

|

||||

|

veteran's day is coming up so...

Mark Stepelton Normandy Invasion I was a young Fighter Pilot flying with the famed 357th Fighter Group stationed at Leiston, England. Our main mission was to escort the 8th Air Force Bomber Force on missions deep into Germany. We flew the greatest fighter plane of World War II, the P-51, Mustang. Our performance was outstanding. We had flown many combat missions prior to June 6, 1944, during which time we had saved thousands of lives of Bomber Crews on long combat missions over enemy territory. Our fighter crew losses were serious and we all wondered when the Invasion would take place. Upon returning from a combat mission on June 4, 1944, we were told that our P-51s would be in a grounded condition temporarily. Little did we realize the magnitude of coming events. Our ground crews began painting white stripes on the wings of our Mustangs and even then we didn't realize those stripes would soon be recognized as "D" Day stripes. The purpose was for our ground troops to easily recognize our aircraft as friendly planes. When not flying, our favorite meeting place was the Officers Club, so it was there, at about 9:00 P.M. or 2100 hours military time on June 5th 1944, that an announcement was made that all combat flight officers would report to the Group Briefing Room immediately. Of course, the excitement was tremendous. No previous combat briefing had created this much attention, even our first mission over Berlin, Germany. Identification was required at the Group Briefing Room and one could feel that something tremendously vital to us was about to take place. We were seasoned combat pilots by now and had seen many fine friends lost in combat. We felt confident in our abilities as fighter pilots to succeed in any mission assigned to us. We were called to "attention" as our Fighter Group Leader entered the briefing room. He immediately requested the Intelligence Officer to first brief us about the "Top Secret" aspects about the mission we were about to hear. We were sworn to secrecy. We were not to tell our ground crews or talk to anyone. Phone calls were "off limits." Our Group Commander then made a very terse announcement that we had been assigned to fly cover for the greatest of all combat missions, the "Invasion of Europe" by our combat ground force enroute by sea. This mission would be called "D" Day and to begin during the early hours of June 6, 1944. I well remember a feeling of supreme excitement, similar to the feeling I'm now experiencing as my mind races back to those indescribable events. We were all young men who, a few years before had never dreamed of being given such a vast responsibility. Our assigned mission was to protect the Normandy Beachhead from attack by German Fighters. The ground combat troops would be asked to invade France against seasoned German Troops. Only a few of our ground troops had combat experience and needed to be assured that the only aircraft above them would be friendly. The Group Commander ended the briefing by stating that we should retire soon as possible because a specific mission briefing would be held at our Squadron briefing room about 2:00 AM. How could we possibly sleep with such a tremendous mission soon to be our responsibility? I couldn't sleep. I laid down on my cot, fully dressed in my flight suit and sought the help of our Lord Jesus Christ. I prayed for the safety of the thousands of young men in ships, waiting for the signal to board their landing crafts. I had no thoughts or concerns for my safety, I already had 38 combat missions. I didn't look at my watch when an officer entered our room and quietly told us to report to the Squadron Briefing Room immediately. Now the excitement was beyond description. Only combat pilots were allowed at this briefing. The Squadron Commander (The worlds best) Lt. Col. John Storch of Long Beach, California, gave us individual assignments in specific areas along the Normandy Invasion Areas. We noted that a light rain was falling and the sky was very black, however, all of England was on a "blackout." Due to weather conditions, we would fly to our assigned areas in pairs. My great buddy, Captain Leroy Ruder from Nekoosa, Wisconsin, would be my partner. Of course, you realize that a P-51 Mustang holds only one person, so we would take off in pairs and be on our own from the moment of takeoff. After synchronization of watches, we received our assigned "start engine" time. We raced to our revetments where our planes were parked and sporting a new set of white stripes on the wings. I carefully checked my plane which I had named "Lady Julie." She was no lady. My Crew Chief and Armorer knew that something extremely important was about to happen because we had never taken off at this time of the night. No questions were asked and the only comment made to me by my Crew Chief, as I sat strapped in my Mustang, patting me on my back he said, "take care of yourself." Waiting for "start engine" time always allowed time for reflection of your lost buddies, and fond memories of times back home. I was never afraid of being shot down. Previous "dog" fights had given me self confidence. The sound of Rolls Royce Merlin engines of our P-51s barking as they were energized, jolted me back to realization of the job ahead. Captain Ruder began taxiing to the takeoff runway ahead of me. The nose of the P-51 is so long that it was necessary to "s" turn the aircraft in order to observe the aircraft ahead of you. We finally reached the area of the takeoff runway, turned the aircraft so as to avoid damage to the plane following you and went thru the "takeoff" check. My engine roared to a high pitch, sweet sound found only in the Merlin engine. Rain now was rather severe. No turning back due to bad weather on this mission. Captain Ruder taxied to takeoff position and I joined him on his right side. He motioned to me with a forward motion of his hand and with full throttle we raced down the runway and up into the black night. Captain Ruder turned out over the North Sea and headed southwest toward the greatest event of our history, the "D" Day Normandy Invasion. Captain Ruder was an "Ace" and a very fine fighter pilot. He was one of those pilots who was extremely confident of his capabilities and was not afraid of anything. We timed our approach to arrive over Normandy before dawn. We dropped down from our flight altitude to a very low altitude as we began our patrol. NO GERMAN FIGHTER PILOT WOULD APPROACH THE LANDING INVASION AREA OF OUR RESPONSIBILITY. As dawn slowly arrived, we could see the vast armada of ships heading toward Normandy. A sight that is etched in my memory for all the days of my life. I prayed hard for the safety of our invading troops. I cannot begin to describe the picture before my eyes, so vast and powerful looking. Large Battleships firing toward shore. After about four hours of patrolling, Captain Ruder called me over the radio to state he had been hit by ground fire and was going down. We were not in close formation. He crash landed and died soon thereafter. The loss of my friend, Captain Leroy Ruder was so shocking because it happened so fast and it was beyond his ability to avoid. I now patrolled alone with a very heavy heart. Captain Leroy Ruder, a very brave and experienced pilot, always extremely aggressive against German Fighter pilots, now lost his life during the early phase of "D" Day. He was the only Fighter Pilot in our Fighter Group and the entire 8th Fighter Command to lose his life on "D" Day. Finally, as my fuel became dangerously low, I returned to our base at Leiston, England. I had logged the longest combat flying time of our pilots on the first mission and could barely climb out of my cockpit. The cockpit of a P-51 Mustang is very confining and not a place for anyone who is claustrophobic. I was the last fighter pilot of our Group to arrive back at our home base from that momentous first mission. After debriefing, I went directly to my barracks and slept for two hours. I was awakened by an announcement that we should assemble at the Squadron Briefing room in 45 minutes. I had not undressed and was still in my flight suit. Even though I was extremely tired, the excitement of this great day dept us young pilots living on adrenaline. At the Squadron Briefing, we learned that we would patrol back of the German lines behind the "beachhead" and to destroy anything moving toward the front. About an hour later, we were back in our P-51's for an "Area Support" mission on this great day. We located a train moving toward the invasion area. We circled the train at a very low altitude, knowing that anything moving was the enemy. The engineer had pulled the engine into a tunnel, leaving the passenger cars exposed. While making a circle, our engine noises alerted the German troops who flooded out of the cars into the area next to the cares. We knew what we had to do, so these German combat troops never reached the invasion area. After several hours of patrolling at low altitudes, we returned to our base at Leiston, England. I was totally exhausted as my Crew Chief helped me climb out of my cockpit. Now it was dark and raining. After debriefing, all I could think about was sleep. I had logged this combat mission at 5:25 hours, some what less than my first mission. The combat troops in the invasion area had no place to sleep. This is the first time, I have attempted to write about the most important day of my life which is so deeply etched in my mind. While our job was exciting and dangerous, EVERY AMERICAN OWES GREAT HONOR AND THANKS TO THE VERY BRAVE COMBAT TROOPS WHO HAD THE TREMENDOUS RESPONSIBILITY OF ACTUALLY INVADING INVINCIBLE EUROPE CONTROLLED BY GERMANY UNDER THE MAD MAN, HITLER. WE AMERICANS CANNOT BEGIN TO THANK THOSE TROOPS ENOUGH. JUST VISIT THE AREA ABOVE OMAHA BEACH, WHERE THOUSAND OF AMERICAN SOLDIERS ARE RESTING AND IT WILL TEAR YOUR HEART OUT.

__________________

|

|

#173

|

||||

|

||||

|

June 29, 1944 Rescue

Captain Mark Stepelton, 364th Fighter Squadron This date, June 29, 1944, is one of the most memorable of my combat tour against the Germans. Our mission was called RAMROD, which meant we would provide fighter protection for B-17 heavy bombers who will attack targets in Leipsig, Germany. The target was heavily protected with flak and German fighters. Arriving in the target area, German fighters attacked our bombers in force, trying to score victories. Our fighters followed the Germans leaving the main bomber force unprotected. After talking to crews of our bombers, pleading with us for fighter protection, a few of us climbed to the area where we could see activity. The few of us had split up. I destroyed a FW 190 and decided to escort bombers until my fuel became quite low, at which time I headed toward England. Upon reaching our base at Leiston, England, I was immediately picked up and taken to operations where our Squadron Commanding Officer, Lt. Col. John Storch, announced that he had just received an urgent message that a B-17 bomber is down in the North Sea off Holland, where some German fighters are firing at the crew of ten men. Col. Storch asked if I would refuel and immediately takeoff and receive flight instructions from our base locator section. I took off alone and was contacted by the English Air-Sea-Rescue unit for further directions. As I approached the area where the aircraft was just slightly in view, I saw men in their dinghy's (small life rafts). As soon as the German fighters became aware of my approach they evidently thought that more than one of our fighters was enroute, because they immediately ceased firing at our crew and headed east toward Holland. I remained with the men until I observed the Air-Sea-Rescue team approaching. I returned to my base at Leiston feeling that we saved the lives of ten bomber crewmembers. Between the Leipsig mission of 4:35 and the Air-Sea-Rescue mission of 3:10 hours, my total flight time for that date was 7:45 hours. On July 14, 1944, near Lyon, France, I participated in a very important " Top Secret" mission protecting 8th Air Force Bombers while dropping supplies to the underground forces called the "Maquis". French underground forces caused serious problems for Germany by destroying many ammunition dumps and troop trains taking men and supplies to the German front. Some of our troops assisted the "Maquis." We dropped our troops (special) by parachutes at designated locations Our Squadron (364th FS) was selected to protect at all costs the 359 8th Air Force Bombers who were dropping supplies via parachute from a very low level flight, about 500 feet. We were told that we must destroy any German Fighters who might report the "Maquis" activities. My wingman, Lt Reed and I were attacked by 20 FW 190 German Fighters. A dogfight resulted at tree top level. As I got on the tail of two Fighters, they split up and I chased a long nose FW190 west and finally got close enough to fire a burst from my machine guns. My shells started hitting his aircraft at the tail and up to his cockpit. His aircraft hit the ground and exploded. I claimed that victory. Our mission finished, we resumed our escort of the bomber force back to England. We were never given credit for that mission. My flight time for that very important mission was six hours. 5. Disastrous Combat Mission, March 5, 1944 After a very long mission escorting Bombers to and from Berlin, Germany yesterday, we logged 5.5 hours and lost Mederious, a Flight Leader. And now Flight Headquarters selected our 357th Fighter Group for another long mission. This March 5, 1944 mission was given the orders to attack targets in Bordeaux, France area, mainly the German Bombers that are devastating our shipping in the Atlantic Ocean. We encountered a vast amount of resistance from enemy ground fire and there was much fighter activity and at one point a pilot (ours) said, "Hi Fellas, I just got hit, and have to bail out." This pilot was Chuck Yeager. A new type long nose FW190 had got on Yeager's tail and shot him up. We searched the area to make sure that Germans had not picked up Yeager. After some additional damage was done our commander, Col. Spicer said, "Lads, let's go home." I was flying Lt. Col. Hayes wing as we headed toward England. Col. Hayes was our Squadron Commander. It appeared that Col. Spicer had damaged his plane on the strafing runs and now announced he was having considerable trouble keeping his plane in the air and would have to bail out quite soon. The Colonel was over water, as we were, and we told him that we would request the English Air Sea Rescue to pick up the Colonel. He had gotten into his dinghy and was paddling out to sea. He was not going to give up. Lt. Col. Hayes ordered a flight to go to our base at Leiston, refuel and rearm and return to the area where Col. Spicer was down, so to give him cover while we waited for the Air Sea Rescue boats. We were getting low on fuel so we had to return to Leiston. Upon arrival we expected to refuel and return to help cover Col. Spicer. Our Group Executive Officer had advised our Fighter Wing HQ, who refused to allow any of us to return to the area where Col. Spicer was down. An International Red Cross message was issued for the Germans to pickup Col. Spicer. The Colonel became CO of a POW Camp in Germany. The Air Corp's lost the finest of all Fighter Pilots for the duration of the war. Colonel Russell Spicer was so mistreated by the Germans that he passed away a few years after WWII. Our loss was great!

__________________

|

|

#174

|

||||

|

||||

|

Perhaps humorous, definitely not heroic, my experiences are very likely typical of a great many of us who were fortunate enough to be there at time, ready and eager to perform the mission. You have probably scanned the book to see where and if I am mentioned. I am not.

I arrived in England in September of 1944 and returned a year later in September of 1945. As far as Air Combat is concerned, I think the best way to express it is that basically when they were up, I was not! Or if they were up, I was escorting someone home, as on the date of December 24, 1944. I was Dollar Blue Two, flying Kirla's wing and was assigned to escort Chuck Weaver who had a rough engine, back to base 30 minutes or so before the group got into a big fight. Or I was screwing up as on the biggest day of them all January 14, 1945, when the 357th Fighter Group got a record 56.5 air victories. On that January 14th mission, I flew someone else's airplane, which had a record of aborting on its tow previous missions because of excessive fuel usage. I had a thing about never aborting and never did. I had not seen any enemy aircraft on so many previous missions, I thought we would not see any on January 14, so I very stupidly kept my fuselage tank full so I would have plenty of fuel and not have to abort when the squadron dropped it's external tanks. On that day, as on most days, I flew with my Flight Commander John Kirla on his wing. He had me convinced that we were going to become another Godfrey and Gentille team. George Behling was Element Leader with Jim Gassere on his wing flying number four position. Behling became a POW that day. Kirla got four victories and Gasser got two. On his first turn into the enemy aircraft Kirla lost me, his hot-shot wingman, who had snapped uncontrollably out of the action. You really can't fly the P-51 with full fuselage and make high G turns at altitude without snapping. The amount of fuel in the fuselage tank affected the center of gravity. After my snap and dive there seemed to be no one in sight except the enemy 109 working its way into firing range on my tail. This of course, with my attitude, gave me a sure victory. I felt I had him all to myself. Two snaps later, I was on the tree tops with full mixture, full throttle to burn that fuselage tank down. My 109 apparently had some positive feelings about me because he was still in the relative position. A flight of four P-51s dropped in on his tail in front of me and shot my victory from the skies. There is more of interest to that day. I next proceeded to fly up to the bomber stream to see what I might do. Incidentally, there was smoke and debris all over the place on the ground from the many aircrafts that had gone in. On reaching the bomber stream and other wise being alone, my vision telescoped. Something was wrong. My oxygen supply somehow was decreased because of all the violent snaps or perhaps more likely I was suffering from hyperventilation. I don't know, but the next thing I do know, I was again at tree top level. I had passed out at 28000 feet and recovered in level flight at ground level. Lucky Boy! At this point I picked up my average course for home and proceeded to fly out across the channel very much disgusted with myself. In route, I did a couple of rolls at a few hundred feet over the channel feeling that if the aircraft went in - so be it. I emptied my guns at various wave tops. Returning to Leiston-Saxmunden, our home base, where victory rolls were being performed, it seemed, by everyone else. ON the ground pictures were being taken of all those who had experienced victories. Jack Dunn did not participate. Ten days or so later the group gathered in the Post Theater to see film form the great mission. In about the middle of the showing and after John Kirla's film showing him gloriously getting four positive victories and Jim Gasser two, here comes film heading "J Dunn, First Lt" I would have left if I could. Someone said "Hey it looks like he must be getting one in the clouds!" Next it was obvious that I was firing into the waves. So you see, all was not heroic, in fact at times very frustrating. John W. (Jack) Dunn Joy Ride The department head's meeting was over, and Major Broadhead, our CO, said the only fair way was to choose numbers. I guessed number one; it turned out to be the lucky one. I had won a ride in a piggyback Mustang! I suppose there have been piggyback P-51's converted before, but some ingenious mechanic in our top-scoring 357th Fighter Group had dreamed this one up by himself. The radio was taken out, the guns were taken out, and an extra seat complete with air speed indicator and altimeter was directly behind the pilot. As a "paddlefoot" usually on friendly relations with pilots, I had gotten quite a few rides, but never in an operational, single-seater fighter aircraft. I've always wanted to ride in one - but I was a little bit scared, too. Major Broadhead, on his second tour and with eight ME 109s to his credit, didn't make me any more at ease by explaining how difficult it would be to bail out. The make-shift canopy may stick, and things happen awfully fast. It seemed that at least half the GI's in the squadron were watching me climb into the ship - secretly hoping I'd get the hell scared out of me. Which - I did. Bob taxied to 06 (the long runway), and before I knew it we were airborne. It was a beautiful day, with a layer of white baby wool clouds at 5,000 feet. Bob climbed up slowly through a hole, although to me the altimeter seemed to be spinning like the second hand of a watch. Then before I knew what was happening, the nose of the ship dropped and the plane seemed to be falling right out of the sky. The aie speed rose..200..250..300..350...and the nose came up again. All the weight of my body seemed to be directly against the seat. Ice water was flowing through my legs instead of blood. My jaw had involuntarily dropped, and I could feel my cheeks and eyes sag like an old man's. I tried to lift my arms; they seemed glued to my lap. This, then, was G strain. Approximately four G's, Bob said later. Now the nose was going straight up. If the altimeter had looked like a second hand before, it looked like a Ferris Wheel now. Before I knew it, we had looped. Not being satisfied with a gentle pullout, Broadhead dropped her on one wing, and did a barrel roll. After a few minutes of straight and level flying (while I got my breath back), Bob decided to hedgehop some clouds. A beautiful layer of white fleece stretched, endless as earth, as far as the eye could see. Toward it we dived, 300 miles per hour. For five minutes Bob indulged in his favorite relaxation of clipping the tops off clouds and turning on one wing. Occasionally the earth would wink at us, or clouds would engulf us from every direction. "Now what would you like to do?" Bob seemed to signal from his cockpit. Ther was nothing I would rather do at the moment than get out and walk home - but that seemed a little impractical. Bob seemed to be making all sorts of "hangar flying" motions with his hand. In my brief experience, that hinted of violent maneuvers to come. Happily, I pointed to a lone fortress at seven o'clock. I thought we might fly alongside and wave at the pilot. Instead, we peeled off and made a pass at him. There turned out to be two forts, and two mustangs were already giving them a bad time. It wasn't long until a flight of four more arrived from nowhere and joined in the fun. It was about that thime that everything from nowhere I had ever heard about "ratraces" was completely forgotten; I was learning from scratch. For a while I kept my eyes on two 51's directly overhead. I looked straight down, and there was the sun. We were up, down and around the bombers - right on the tail of a 51 - on our side, upside down, in a dive, in a pullout, I lost all trace of horizon, airspeed, ground...my head was spinning...the prop was spinning... I was conscious only of the throb of the engine and the occasional flash of an airplane overhead. After a king-size eternity, the ratrace was over, and although I could not see Bob's face, I knew he was grinning from ear to ear. We had been up about thirty minutes. Seeing nothing else of interest, Bob headed "Eager Beaver" for 373. we flew straight and level, on a compass heading, all the way home. I saw a town of around 90,000 from the air, but I couldn't get very interested in it. I felt dead tired, as if I had worked a week without resting and had suddenly stopped. I had the thought that I was dead weight as much as a sack of flour. I wanted to collapse. By the time we arrived at the station I felt much better. The field looked like three toothpicks touching, with the ends overlapping. The altimeter read 8,500 feet. "Fifteen minutes more, and we'll be landing," I thought. bob grinned back at me. More maneuvers with his left had. I nodded agreement, and wondered what would come next. One wing suddenly slipped out from under us, and we were upside down. Little pieces of mud an debris went past my eyes and hit the canopy, I remember thinking they were falling upside down. Then the nose dropped, and we split-essed out, going straight for the ground. The airspeed increased; the earth grew larger. The huge prop was spinning like a man gone mad. I watched the airspeed: 350...400...425. The altimeter was spinning backward like a watch going the wrong way...6,000...5,000...4,000. The earth had never looked so hard. At 2,000 we leveled out, with the airspeed indication 450. After that, the peeloff and landing seemed dull. We had traveled a vertical mile in a matter of seconds, and had reached approximately 550 miles pre hour ground speed. The landing was rough. I tried to swallow, and couldn't. My throat was dry. My hair was tousled, my legs were cold, my face was white, and I was glad to be on the ground. Thanks to Major Broadhead, that was forty-five minutes of my life I'll never forget. And each time I remember it, the more I enjoy it! By Paul Henslee, 362nd FS Adjutant and Executive Officer

__________________

|

|

#175

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

And do me a favour, look up Frantisek, see how badly he did in his short time in the seat of a hurricane. Apologies Bobby for marring your thread but this sort of xenophobic rubbish anoys me especially within a thread that is dedicated to preserving the memory of these few true heroes. Last edited by Gilly; 11-01-2010 at 10:50 PM. |

|

#176

|

|||

|

|||

|

I meant the Polish planes, you know? Those things made of tinfoil, wood, and strings. The Polish had good pilots, but their own planes were bad. The PZL P7 is similar to a I-153, only its a monoplane.

|

|

#177

|

||||

|

||||

|

not my thread just started the ball rolling...anyone can contribute. the russians used hurris and p 39s at the onset like 40 and 41. they dug one out of a bog years ago along with pilot. not sure where all the battles were at that time but theoretically it is possible for a hurri with a red start to have been over stalingrad. now whether one did or not i wont even venture a guess.

__________________

|

|

#178

|

|||

|

|||

|

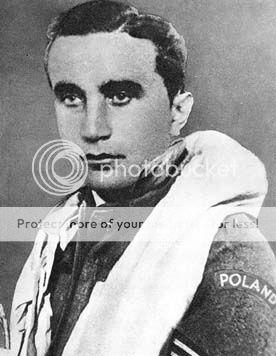

A brief history- sadly not Frantiseks own words but you will see why

Written by Dariusz Tyminski Josef Frantisek was born a carpenter's son in Otaslavice near Prostejov on 7 October 1913. After his initial training as a locksmith, Josef volunteered for the air force, and went through the VLU Flying School in Prostejov in 1934-1936. He was then assigned to the 2nd "Dr. Edvard Benes" regiment in Olomouc. He was with the 5th observation flight flying the Aero A-11, and Letov S-328 biplanes. It was during this time Josef's individualistic attitude first showed. He never had a sense of discipline on the ground. Demoted from the rank of Lance Corporal to Private for late returns to his unit, pub fights and other incidents, Frantisek faced the prospect of being released from service. As an exceptionally talented pilot he was chosen for a fighter course with the 4th regiment, and he stayed with this regiment after completing training. In June, 1938 he was assigned to the 40th Fighter Flight in Praha-Kbely. He was under the command of Staff Captain Korcak, and the pre-war Czechoslovak "king of the air" - Lieutenant Frantisek Novak. Frantisek perfected his flying and shooting skills here, flying Avia B-534 and Bk-534 fighters. During the dramatic events of 1938, the 40th flight was dispatched to several airports around Prague to defend the capital. After the Munich agreement, the flight had to return to Kbely, where it stayed until 15 March 1939, when Czechoslovakia was taken by Germany without a fight. Josef Frantisek wasted no time escaping to neighbouring Poland. On 29 July 1939, preparing to travel to France, Frantisek received a offer to join the Polish Air Force. He arrived at Deblin airbase, and after retraining with Polish equipment, became an instructor with the Observation Training Squadron under the Air Force Officers Training Centre Nr 1. He flew PotezXXV, Breguet XIX, PWS 26, RWD 8, RWD 14 Czapla, Lublin R XIII and other aircraft. On 2 September 1939, Deblin was the target of a huge Luftwaffe air raid. Frantisek had no time to take off with his Potez XXV among the falling bombs. He saw 88 Heinkel He 111s from KG 4 "General Wever" turning the largest Polish airbase into a heap of rubble. Frantisek then left for Gora Pulawska airfield, where, under the command of Captain Jan Hryniewicz, he helped fly the remaining airplanes away from the advancing Wehrmacht. On 7 September 1939, Frantisek and some other Czech pilots were assigned to an observation training squadron at the Sosnowice Wielkie airfield near Parczewo. The unit, commanded by Lieutenant Zbigniew Osuchowski, had fifteen RWD 8 and PWS 25 trainers. On 16 September 1939, after further retreat, the unit was assigned to General of Brigade Skuratowicz to defend the city of Luck. On 18-22 September 1939, they flew reconnaissance and communication flights. For all their bravery and determination, Polish resistance was coming to an end. On 22 September 1939, the remaining six planes flew from Kamionka Strumilowa airfield to Romania. Three of these machines were flown by Czechs. Frantisek flew General Strzeminski in his machine. They landed at the Ispas airfield, and went on through Cernovici and Jassa to Pipera. They were interned, but escaped on 26 September. They got to Bucharest, obtained documents and on 3 October 1939, boarded the steamer "Dacia" leaving Constanta for Beirut. They continued to Marseilles on board the "Theophile Gautier", entering France on 20 October 1940. Frantisek stayed with the Polish Air Force in France, which was part of L'Armee de l'Air. He was retrained at Lyon-Bronand Clermont-Ferrand, where he reportedly test-flew aircraft after repairs. There are conflicting reports regarding his combat activities. Some witnesses claimed Frantisek shot down 10 or 11 enemy aircraft flying with the French. These published reports have never been disproved; yet official French and Polish documents have neither confirmed the claims. Some witnesses recall that Frantisek changed his name temporarily in April, 1940 to protect his family in Otaslavice from persecution by the Gestapo. His cover name is unknown. As long as this question remains unanswered, Frantisek's French period cannot be closed. On 18 June 1940, after the fall of France, Frantisek took a Polish ship from Bordeaux to England. He arrived at Falmouth on 21 June. Frantisek was sent to a Polish aviation depot in Blackpool, and on 2 August 1940 left for Northolt airfield, where the 303rd Polish Fighter Squadron was being formed. The squadron was equipped with "Hurricane" Mk. I fighters and coded with the letters "RF". In one of first training flights on 8 August Frantisek belly landed - he forgot to open the gear in his Hurricane before landing... Luckily the pilot was untouched and his fighter (RF-M V7245) got only light damage. Frantisek scored his first kill under British skies on 2 September 1940. This was very busy day for the 303rd - flying three sorties. In the last one, at 16:35, the Squadron took off with orders to encounter a formation of 'bandits' at 20,000 feet over Dover. In the combat, Frantisek and Sgt. Rogowski scored one confirmed Bf 109 each. The next day, the Squadron took off (at 14:45) and was vectored to Dover, where Frantisek again shot down an enemy fighter for his second kill in the "Battle of Britain". On 6 September 1940, in heavy combat, the 303rd downed 5 Bf 109s, but Polish losses this day were serious: both Squadron leaders (Polish - Mjr. Krasnodebski, British - S/Ldr Kellet) and 2 other pilots were shot down, Frantisek luckily returning in his damaged fighter to Northolt. Three days later, Frantisek was forced to land with a badly damaged "Hurricane". The plane was totally destroyed, but Frantisek got out of it, unscathed. 15th September 1940, was a great day for the 303rd, when its pilots tallied 16 victories against the Luftwaffe, and Frantisek downed one Bf 110 in that action. In only four weeks, from September 2nd through the 30th, Frantisek achieved 17 certain kills and 1 probable . This was a unique achievement in the RAF for this period - bettered only by F/Lt. A.A. McKellar and W/O E.S. Lock. Each of them both had 20 victories, yet both were killed in the "Battle of Britain". It is often mentioned that Frantisek's excellent results were due to his lack of discipline in the air. He often left the formation and hunted for the enemy on his own. He also waited over the Channel for returning German planes, who were often flying without ammo, with limited fuel, sometimes damaged, and with tired crews. This was a usual tactic for Allied pilots, but only after completing all mission objectives. After Polish pilot mission briefings, Frantisek often disappeared from 303rd formations just after take-off. Despite higher command warnings, for Frantisek lone-wolf missions were like drugs - and his number of kills grew quickly. As the squadron leader, Witold Urbanowicz was facing an almost insoluble dilemma: either discipline Frantisek (which he attempted several times without success), or have him transferred at the expense of losing squadron pride. Urbanowicz dealt with this cunningly: unofficially declaring Frantisek a squadron guest, which was acceptable due to his Czech origin. The Poles called his tactics "metoda Frantiszka" (method of Frantisek) while the British spoke of the lone wolf tactics. It is by no means true that Frantisek gained all his victories in individual actions - many kills were scored in group missions. The 303rd squadron had 126 confirmed kills in the Battle of Britain - the most successful record for a RAF squadron in this period. Frantisek, with his 17 kills was not only the best pilot of the squadron, but also among the elite of the RAF. Frantisek's sudden death in an 8 October 1940 accident remains incomprehensible, as is the case with some other excellent pilots. Squadron 303 was flying a routine patrol that morning. Frantisek's machine disappeared from the view of his fellow pilots, and he was never again seen alive. At 9:40 a.m. his "Hurricane" Mk.I R4175 (RF-R) crashed on Cuddington Way in Ewell, Surrey. Frantisek was thrown from the cockpit and his body was found in a hedge nearby. At first glance he had only scratches on his face, and his uniform was slightly charred. But Frantisek's neck had been broken in the impact and he died immediately. There has been no definitive cause in the crash of his plane. Some sources say he failed an acrobatic exhibition in front of his girlfriend's house, other witnesses mention his absolute exhaustion from previous fighting. A combination of these two factors is a possibility. His Polish friends buried Frantisek at the Polish Air Force Cemetery in Northolt on October 10, 1940, where he is still resting. He stayed with the Poles forever. Last edited by Gilly; 11-02-2010 at 09:19 AM. |

|

#179

|

||||

|

||||

|

what impresses me about these guys inparticular is they had many chances to escape to no combat areas. they could have take their chances in communist russia...or gone to finland or even neutral sweden. most had trades and could have lived comforatable lives and contributied to their new societies. but they stood and fought for their countries freedom as exiles. and in a lot of cases were thrown in prison after the war by occupying communist regimes who feared their initivite and daring. truely patriots they were.

__________________

|

|

#180

|

||||

|

||||

|

Quentin Aanenson

I guess in one sense you can say we are an endangered species. But unlike the spotted owl or the whooping crane, there is no legislation that can be enacted to save us. We are rapidly disappearing off the radar screen, and soon all that will be left is what we have written, what we have recorded, and some old, fading photographs. Our voices will be forever silent, and the untold "first-hand accounts" of our experiences will remain untold. We are the boys of World War II. We are dying off at the rate of 1,500 a day -- that's 45,000 a month. That number will steadily increase until the unyielding laws of mathematics give us an increasing rate of deaths, but a decreasing number of deaths -- the remaining pool will have become too small. Taps is just one sunset away. But in our lifetimes, we made a difference. We had the good fortune to live during a time when honor, patriotism, and character were important. We stepped up to defend freedom, and put our lives on the line for the "cause." It was a moment in history that may never occur again. It was 1944. I was 22 years old. And I was a combat fighter pilot in World War II. Along with thousands of other young Americans, I had been trained to be an efficient killer, and the deadly skies over Europe were my battlefields. The events of those violent and bloody days are difficult to comprehend, or even imagine. The story you are about to see is the result of the urgings of my children. They have wanted to know -- in specific terms -- what my life was really like during those critical years....those were the years I left college and joined the Air Corps, and met the girl I later married. Those were the years this airplane, the P-47 Thunderbolt, was to be my main weapon of destruction. It has been a traumatic experience for me to go back through all this. But perhaps, in other ways, it has helped purge some of the devastating memories that have haunted me for almost 50 years. So this is my story. It is being told so the children and grandchildren of those who were involved in this mortal storm, can have a better understanding of what our world of war was really like. A Sad Happenstance of War-- Two Stories Become One pt1 On November 17, 1944, the 391st Fighter Squadron of the 366th Fighter Group flew what was perhaps our worst mission of the war. A major ground offensive had begun the day before along the Western Front from the northwest edge of the Hurtgen Forest up through Eschweiler, Germany. The weather was terrible with low hanging clouds and light rain, but we were able to take off with each plane loaded with two 500 pound bombs and a 150 gallon belly tank. Sixteen planes from the 391st were involved in the mission. When we reached the target area, we had to come in under the overcast at 4,500 feet. Everything was dark and eerie – we could see flashes of the big guns on the ground and the flak explosions in the air. Light from the exploding shells was reflecting off the clouds -- it was as if we were looking into a segment of hell. Dive bombing starting from such a low altitude is a challenge in itself, but each of us in turn did our best to hit our target. I was hit in the canopy right behind my head just as I rolled over to start my dive and was hit again as I pulled out of my dive. It was apparent I was in deep trouble as I fought to keep my plane in the air. In the meantime, the other 391st pilots were fighting for their lives. Lt. Rufus Barkley dived to strafe a German vehicle, and flew into the ground and exploded. Two of my tent mates, Lt. Richard "Red" Alderman and Lt. Gus Girlinghouse attacked a column of tanks and trucks along a road near a castle on the edge of the Hurtgen Forest, and both were shot down within seconds of each other. My radio was out of commission, my controls were damaged, and the engine was barely generating enough power to keep me in the air. When I had crossed the front lines, I kept my eyes open looking for some clear space where I could belly in, if the engine gave out. By pure luck I came upon an American landing strip that was under construction, and was able to get my damaged bird down on the partially built runway. When I got back to my base several hours later, I was listed on the pilots' board as "Missing In Action." The loss of my two tent mates was devastating. "Red" Alderman and I had gone through all our training together, and were very close friends. He had given me the farewell letters he had written to his wife and his mother – I was to mail them if he were killed. Lt. Gus Girlinghouse had just moved into our tent, so I was just getting to know him. The night of November 17, 1944, was the worst night of the war for me. pt2 On December 16, 1944, heavily reinforced and upgraded German Armies attacked the American lines from the Ardennes, and the biggest battle of the war on the Western Front began, "The Battle of The Bulge." The weather was so bad that most of our planes were grounded for about a week, and the Germans were able to advance about 40 miles into Belgium. On December 24th we were briefed for a mission and sitting in our planes waiting for the weather to improve, when our Operations Officer pulled up to my plane in a jeep. He told me orders had just come in for me to report to the Headquarters of the VII Corps, and that a staff car was coming to pick me up. Within a few hours I was on my way to this new assignment. My new job was to coordinate all fighter-bomber attacks in front of the Divisions of the VII Corps. This was a major change for me; instead of doing my fighting from the air, I was now on the ground, and very near the front lines. Ground fire, such as artillery barrages, mortar fire, rifle and machine gun fire were now part of my life, instead of flak and the normal high risk of flying a fighter plane. As our armies advanced, pushing the Germans back, we moved our headquarters frequently to stay close to the front. Around February 18, 1945, we moved into Merode Castle, about three or four miles from the town of Duren on the Roer River. The castle had been built in the Middle Ages. It was surrounded by a moat, and had several staircases leading up the circular towers to the ramparts, where archers in centuries past had defended the castle. Nothing about the area seemed particularly familiar to me, except that I knew I had flown several missions to attack German targets in this vicinity, especially during November. We were there now making preparations for a major attack to cross the Roer River, capture the town of Duren, and reach the open plains leading up to the Rhine River. The photograph below shows me in front of the main entrance to the heavily damaged castle about two days before the battle was to began. When this photograph was taken, I had made no specific connection with the events of our combat mission flown by the 391st Fighter Squadron on November 17, 1944. Then in 1995, Robert V. Brulle, who was also a member of the 366th Fighter Group, wrote a story describing the terrible mission we flew on November 17, 1944. It was published in "World War II" magazine, and included vital new information that Bob had secured from German sources, some of it from a German officer who had been involved in the battle that day, and actually commanded the flak guns that shot down Lt. Alderman and Lt. Girlinghouse. He had seen their planes crash, and was able to mark the exact location of impact. Before he moved his men and their flak guns out of the area, he ordered other German soldiers who were at the site of the crashes to bury the American pilots. It is difficult to conceive that the machinations of war had placed me at Merode Castle three months after that terrible mission, and that my good friend, Lt. "Red" Alderman, was buried about 100 yards in front of where I am standing in the photograph above! It is equally unbelievable that one of the German guns that shot him down was firing from the drawbridge of the castle shown behind me in the photograph. Had I known at the time that he was buried there, and that my other tent mate, Lt. Girlinghouse, was buried about 800 yards farther out in the fields, it would have torn me apart. And to think that this information was not known by me until 50 years after these events took place. ************************************************** ************** EPILOGUE Even though the German soldiers had buried Lt. Alderman at the site of his crashed plane, his body was never recovered. About ten days after he was buried a tank battle took place on the same ground, and all markings of a grave site were destroyed. His name is listed on the "Wall of The Missing" at the Netherlands American Cemetery near Maastricht, Holland. I visited this cemetery a few years ago, and touched the place on the wall where his name is engraved. Several times over the years since the war ended, I had tried to locate "Red" Alderman's children, but without success. When he was killed, his daughter, Lynn, was 15 months old. Then three weeks after his death, his second daughter was born, Cecilia Ann. I thought they would like to know something about their father -- what a fine man he was, and what an excellent fighter pilot he was. I had no luck in my search until the film I wrote and produced, "A Fighter Pilot's Story," was shown in the area where they live near Seattle. Since then I have communicated with them, and have met and had an extensive personal visit with Cecilia Ann. I have been able to fill in some of the blank spaces, and help the Alderman girls know more about their father. The Endless Trauma of A Deadly Combat Mission It was late August 1944, and Patton’s Armored Divisions were in a mad dash to the Seine River, trying to catch the rapidly retreating Germans before they could escape. I was flying in a flight of four Thunderbolts patrolling the Seine to do everything we could to prevent their crossing. Up to this time most of the Germans had been crossing at night to escape our attacks, but on this particular day – with Patton’s tanks rapidly approaching them – the Germans were forced into trying to cross during the daytime. It was late afternoon near the town of les Andelys when we suddenly spotted them. What happened during the next 10 minutes will stay fixed in my memory as long as I live. The German troops were crowded on barges, in small boats, just anything that would float. We caught the barges in midstream, and the killing began. I was the third plane in the attack, and when I pulled in on the target a terrible sight met my eyes. Men were desperately trying to get off the barges into the water, where large numbers of men were already fighting to make it to shore. My eight .50 caliber machine guns fired a hundred rounds a second into this hell. As the last P-47 pulled off the target, the first plane was making its second strafing pass, and the deadly process continued. In about three passes we had used up our ammunition, so we pulled up and circled this cauldron of death. I don’t know how many men we killed that day, but the numbers had to be very high. All of the pilots were quiet as we flew back to our base in Normandy – there was no radio chatter. We each shared the agony of what we had just done. We were traumatized, but there had been no other option. If we had let them go, we knew that they would be killing American boys in a couple of days. In my nightmares I still vividly picture that scene. After more than 50 years, it still haunts me. I deal with it, but think for a moment what it must be like to have to deal with it. There is no glamour in war. You kill people – and you see your friends die. The only honor involved is what you yourself bring to the process. You try to do the job you know you must do – and you try desperately to keep your sanity. But you are forever changed. You are no longer young; in a matter of months you have aged years. Though you have physically survived, you have lost more than life itself; you have lost part of your soul.

__________________

Last edited by bobbysocks; 11-02-2010 at 07:45 PM. |

|

|

|