|

|

|||||||

| FM/DM threads Everything about FM/DM in CoD |

|

|

|

Thread Tools | Display Modes |

|

|

|

#1

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Quote:

Quote:

Quote:

Quote:

Quote:

Quote:

Quote:

Here is the link if you have difficulty remembering http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk:Ai...tle_of_Britain What is missing from your tirade is any evidence to support your theory that the RAF wasn't effectively fully equipped with 100 Octane. All you have tried to do is distort other peolpes document supporting that theory. PS do you still stick by Pips postins as the basis of your argument. If you don't then what is the basis of your argument? Last edited by Glider; 06-18-2011 at 10:24 PM. |

|

#2

|

||||

|

||||

|

Could you two fight this out via PM????

That would be a relief for this topic as your post are OT! Talk about performance and not the reasons why or why not it was reached.

__________________

Win 7/64 Ult.; Phenom II X6 1100T; ASUS Crosshair IV; 16 GB DDR3/1600 Corsair; ASUS EAH6950/2GB; Logitech G940 & the usual suspects  |

|

#3

|

|||

|

|||

|

Frankly I don't understand what are those ppl hijacking a game forum - that shld be dedicated mostly to young players - to rage a war that seems to count countless uneventful battles.

Now as I am not that much hypocrite I will tell you what I am thinking abt this debate that as lasted too long : Firstly : Historically in none of the book that I hve read so far (and I hve read nearly a thousand on aviation field) have mentioned the fact that BoB RAF's Spitfire fleet did use 100oct Secondly : none of you 10Other care much abt the Hurri despite that we know pretty well what Dowding fear most and the fact that Hurri were at that time accounting for two third of the RAF order of battle Thirdly : your arguments (boost for HP and speed) regarding the use of 100oct does not fit any mechanical logic regarding the subsequent dev of the Merlin Fourthly ; your over aggressive comments in such a sensitive time of history does not honor the fighting spirit of those "few" hundreds of men that didn't hesitate to make the ultimate sacrifice without loudly putting their case to the public(at least when all the pint of beer and bottle of whiskey stand at bay) Fifth : The arguments you provided against does not convince us as much as those advocating the other thesis. If you can't prove that something does exist you can't say that it's a truth. Only believer can agree in certain case but I am sry to say that your lack of poetry and chivalry deserve your meaning. Let's resume : 1st. We can say that some Spit and Hurri did rely to 100oct latte in BoB in frontline units. 2nd We can assume that 100oct was used on low alt raider bombers - perhaps "the some of the spits" were low alt escorting fighters. This makes more sense that 100oct being used at alt high fight (were BoB did occur : Bob was an anti-bomber campaign for the RaF !) 3rd The value for the HP provided are grossly overestimated and only focused on the Spit witch does not makes any sense as Spit and 109 were much close match and it seems to be well known for years 4th the Spit FM in CoD is so ridiculously CFS friendly that your lack of any ref to this fact makes your thesis very suspicious. If realism, impartiality and accuracy were your credo you sincerely miss there a strong opportunity to lift your case. 5th Average reader here (and I am one of us) does not know what are your anger against Kurf (with who I hve not particular preference but who did provide us better analysis in term of logics IMHO) but let me say that many of us does not approve any public hanging. In Eu these are( or must stay) facts of the past as are Nationalism, racism and revisionism...Thx so much to the very "Few" (and sadly millions of others) I hope this sterile debate wld be close on this forum for now. If you hve read all this text so far, thx for the time spent. Pls be assured that I don't want to hurt anyone based on quickly typed arguments on a public game forum. We are not historians. ~S! |

|

#4

|

|||

|

|||

|

I will drop the agression and let the documents speak for themselves. The reason I went into this debate was to try and ensure that when you model the aircraft for the sim you need to ensure that the RAF fighters are equiped with 100 Octan performance.

If you don't then you stand a very high chance of being ridiculed by some very knowledgable people who will want to know what the evidence is. Whatever the comments some vital documents have not been questioned so I will only touch on those here. The stocks of 100 Octane were very significant and grew during the battle to approx 400,000 tons by the end of the battle at a time when consumption was only 10,000 tons a month on average between June and August so there was no shortage of the fuel. We know that the changes to the engines to use the fuel were small and the performance gains substantial and we know that 30+ squadrons used the fuel including units in France and Norway. It was 30+ not because we only found 30+ squadrons but because we only looked at 30+ squadrons. I am very confident that if we looked at the rest we would find the same but cannot guarantee it Although said with vigour, my postings have been honest and as complete as I can make them. Look at the explanations I have given in a cool light and you will see that where I don't know I have said I don't know for instance where the original papers said certain. Where I have made an interpratation I have tried to support it and explain why I made it. An example being the request from the ACAS which was clear but the Oil Committee members said proposal and certain. In these cases you need to look at both papers not just the one. I don't know which books you have read but if you go to any bookshop or look online you will find a number of books that cover this topic and all of them agree with the proposal that the RAF did equip fighter command with 100 Octane. If you want to send me a PM I will supply some suggestions but don't want to lead you. If you want a balanced view ask Kurfurst and he mght be able to suggest some. I would be interested to know what he suggests. I do believe that those who don't believe that FC wasn't fully equipped have not put forward any evidence relying on a misinterptritation of the papers put forward by myself and others. You may want to check out those links I gave to Wikki and the WW2aircraft site to get a feel for things and additional information. Once again I suggest you think long and hard before distributing a product that doesn't have the RAF with 100 octane as standard for its fighters. Last edited by Glider; 06-18-2011 at 11:45 PM. |

|

#5

|

|||

|

|||

|

Salute

What is clear is we have an individual, Kurfurst, (who hides his real name) and who has been banned from two respected sources for information on the subject, Wikipedia and WWII Aircraft Forum, during similar debates, and for behaviour inappropriate and claims which cannot be substantiated. Now he is repeating the same claims and commentary here, again without substantiation or documentation. If anyone chooses to believe there is veracity in his posts, then I guess that is their right. |

|

#6

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

__________________

Il-2Bugtracker: Feature #200: Missing 100 octane subtypes of Bf 109E and Bf 110C http://www.il2bugtracker.com/issues/200 Il-2Bugtracker: Bug #415: Spitfire Mk I, Ia, and Mk II: Stability and Control http://www.il2bugtracker.com/issues/415 Kurfürst - Your resource site on Bf 109 performance! http://kurfurst.org

|

|

#7

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

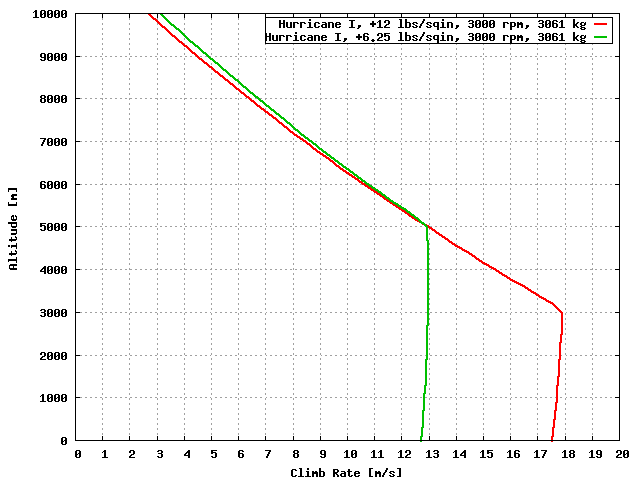

2) All Merlin engined fighters saw a tremendous increase in climb rate due to the use of 100 octane fuel, when using the combat rating of the engine:  for example, the Hurricane I's climb rate increased to ~3450fpm up to 10000ft and the time to 20,000ft declined to about 6.5min at 12lb/3000rpm from 9.75min at 6.25lb/2850 rpm at 6750lbs. The increased climb rate paid dividends even though the performance above ~16,000 ft was unchanged with 100octane fuel. On the later Spit V at 6965 lbs, the combat rating climb performance was: .(a) Climb performance. Combat rating 16lb boost@3000rpm / Normal rating 9lb boost@2850 rpm. Maximum rate of climb (ft/min) 3710 at 8,800 ft/2650 at 14,900 ft. Time to 10,000 ft. (minutes) 2.7 / 3.8 Time to 20,000 ft. (minutes) 6.15 / 7.9 min http://www.spitfireperformance.com/aa878.html 3) There was a considerable increase in performance for both the Hurricane and Spitfire. |

|

#8

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

I notice the lack of meaning in your posts, Glider. You are become increasingly rhetorical. You want people to disprove you, after you have failed to prove your point.

Even when you kept posting the same papers - five times on every page - that say only a portion of Fighter is using 100 octane was better. Quote:

Quote:

Ie. Vincenzo wrote: "I read the docs in none it's write that 100 octane was in use in all the stations/squadrons (for hurri and spits), the docs clear that all spist and hurri can use the 100 octane fuel also with the engienes were not modified (but with no benefit). if i miss some show me." Mkrabat42 also disagreed with you, and simply said that you only listed circumstantial evidence, but no solid proof to your case, and solid historical methods require things that you simply do not have. Quote:

Quote:

Quote:

Nobody misrepresented the real Gavin Bailey's paper, you can read it here below. It again says that select Fighter Command stations were fueled with 100 octane. Quote:

Quote:

Quote:

Quote:

__________________

Il-2Bugtracker: Feature #200: Missing 100 octane subtypes of Bf 109E and Bf 110C http://www.il2bugtracker.com/issues/200 Il-2Bugtracker: Bug #415: Spitfire Mk I, Ia, and Mk II: Stability and Control http://www.il2bugtracker.com/issues/415 Kurfürst - Your resource site on Bf 109 performance! http://kurfurst.org

|

|

#9

|

|||

|

|||

|

Gavin Bailey wrote the following on the subject - I am not going to post here the whole article, as this would reasonably hurt the actual writer's interest, but the relevant part, permissable under free use; if anyone doubts anything significant was left out, contact me in PM.

"Similar figures at the intersection of the military and industrial spheres were to perform an identical role in advocating the adoption of 100-octane fuel in Britain as they did in the United States. As the USAAC moved towards the adoption of 100-octane, Klein's article was circulated in the Air Ministry and Rod Banks outlined the possible operational importance of the fuel in a paper delivered to the Royal Aeronautical Society and Institute of Petroleum in January 1937.27 Apparently as a direct consequence, the Air Ministry specified that future engine development should incorporate the capacity to use 100-octane fuel. Contracts were placed for the delivery of substantial quantities of 100-octane fuel, amounting to 74,000 tons of iso-octane per year from three supply sources, including one in Trinidad outside United States control.28 By the end of 1937, the Air Ministry had accepted 100-octane as the future standard for the RAF, and by early 1938 it was decided that the authorised war reserve stock of fuel was to be composed of as much 100-octane as possible.29 Significantly, at the same time as the British were preparing to take these preliminary steps required to utilise 100-octane fuel, a committee was formed consisting of representatives from the leading oil companies, Imperial Chemical Industries and Air Ministry officers. Chaired by Sir Harold Hartley, the chairman of the Fuel Research Board, the objective of the committee was to recommend measures to ensure that adequate supplies of 100-octane fuel could be supplied in wartime.30 The immediate impetus behind this development was the possibility that the main existing source of supply"”hydrogenation plants run by Standard Oil and Shell within the United States"”might become inaccessible owing to the embargo requirements of the US Neutrality Acts on the outbreak of war. A further consideration was the fact that 100-octane supplies were purchased in dollars in the case of Shell and Standard Oil production in the United States and in Dutch guilders for Shell production from Curacao in the Netherlands West Indies and later on from the Netherlands East Indies. This presented a potential problem for British balance of payments and foreign currency exchange which was only resolved in the short- and medium-term future by the adoption of supply under the terms of lend–lease in 1941.31 The Hartley Committee eventually determined in December 1938 that three new hydrogenation plants should be funded partially at government expense in Trinidad and in Britain to expand British-controlled annual 100-octane fuel production capacity to 720,000 tons above the level already in prospect from existing supplies. At this point Shell and ICI had co-operated to build the first hydrogenation plant in Britain at Billingham on Teeside and further plants were being planned at Stanlow in Cheshire by Shell and Heysham and Thornton in Lancashire by the Air Ministry.32 In January 1939, when the Hartley Committee report was adopted by the Committee of Imperial Defence, the Treasury was able to cancel one of the planned plants in Trinidad on the grounds of cost, in return for an expansion of the authorised war reserve from 410,000 tons to 800,000 tons, 700,000 tons of which were to consist of 100-octane. This represented an entire years worth of estimated consumption on the basis of the major expansion and production schemes then in force and required an enormous investment in building the required protected underground storage infrastructure.33 RAF tests with 100-octane had begun in 1937, but clearance for operational use was withheld as stocks were built up. In March 1939, the Air Ministry decided to introduce 100-octane fuel into use with sixteen fighter and two twin-engined bomber squadrons by September 1940, when it was believed that the requirement to complete the war reserve stock would have been met, with the conversion of squadrons beginning at the end of 1939.34 By the time war broke out, the available stocks of aviation fuel had risen to 153,000 tons of 100-octane and 323,000 tons of other grades (mostly 87-octane).35 The actual authorisation to change over to 100-octane came at the end of February 1940 and was made on the basis of the existing reserve and the estimated continuing rate of importation in the rest of the year.36 The available stock of 100-octane fuel at this point was about 220,000 tons. Actual use of the fuel began after 18 May 1940, when the fighter stations selected for the changeover had completed their deliveries of 100-octane and had consumed their existing stocks of 87-octane. While this was immediately before the intensive air combat associated with the Dunkirk evacuation, where Fighter Command units first directly engaged the Luftwaffe, this can only be regarded as a fortunate coincidence which was contingent upon much earlier decisions to establish, store and distribute sufficient supplies of 100-octane fuel.37 While much of this total stock had originated from production in the United States, the actual anticipated sources of supply assessed one month later and given in Table 3 indicate the actual diversity of supply which allowed operational use to go ahead. View this table: [in this window] [in a new window] Table 3: Revised forecast of 100-octane fuel stock position: supplies due between 1 April 1940 and 31 December 1940 (figures in tons per annum) It can be seen that, despite the preponderance of American supply, the extent of the existing accumulated reserve and the anticipated production from non-American sources of 100-octane do not conform to the blanket statements of dependency upon the United States alone which is asserted in many sources. The extent and relative importance of this diversity can be seen in the Anglo-Iranian (British Petroleum (BP)) 100-octane plant in Abadan. The Abadan plant had been built as a private venture by BP and was producing 100-octane spirit which met the Air Ministry specification in June 1940 after production facilities had been expanded at Air Ministry request.38 The first delivery of fuel from Abadan to Britain took place in July 1940, and by the end of the year 23,000 tons had been delivered. The importance of this can be seen from the fact that the total supplied from this single non-American source equates to the issue of 22,000 tons of 100-octane fuel between 11 July and 10 October 1940 by Fighter Command, almost exactly corresponding to the accepted span of the Battle of Britain.39 Shipments from Abadan were later reduced in light of the availability of oil of all kinds from the United States, as the shorter voyage across the Atlantic from America economised on the tanker tonnage required for importation. But it remained a viable alternative to American supply sources. In February 1941 continuing uncertainties over dollar purchasing before the passage of the Lend-Lease Act led to the temporary abandonment of the ˜short-haul' shipping policy to the benefit of supplies from Abadan. This reactive and dynamic process can also be seen in the case of the Shell/ICI hydrogenation plant at Billingham, which produced 30,000 tons of fuel in 1939.40 This plant, and the delivery of further supplies of 100-octane from BP refineries in Iran, provided immediately available substitutes which individually had the contemporary capacity to supply Fighter Command with the quantity of 100-octane fuel expended in the Battle of Britain. Beyond this, the German conquest of the Netherlands in May 1940 had prompted the British to immediately occupy the Netherlands West Indies, where the main Shell and Standard Oil 100-octane refineries were located. The RAF remained alive to the issue of continuing supply into the summer of 1940. When towards the end of August it was suspected that an oil embargo on belligerents might be implemented in US administration policy in response to Japanese expansion in south-east Asia, a further review of existing stocks and future production indicated that stocks of 100-octane had risen to 389,000 tons while more than 75,000 tons could be expected from non-US sources before the end of the year.41 These facts significantly challenge the identification of the United States as the specific national origin of supply of 100-octane in isolation. While the development of 100-octane fuel and the early supplies of it to Britain in 1937–9 were heavily dependent on US production, this cannot be extended to become a critical dependency on American production alone once the extensive steps taken to ensure a diverse and reliable supply which were taken by the British during the period of rearmament are taken into account. The supply of 100-octane fuel to the RAF was the result of technological development initiated in the United States, but it was established and developed in Britain by a partnership of commercial oil companies and government agency within the cohesive framework of pre-war rearmament policy. The United States was the single most important country of origin for RAF supplies of 100-octane fuel in the period 1939–40. Yet British importation plans in 1938 reveal that the United States was expected to contribute nothing to the initial accumulation of the war reserve up to March 1939, with the available storage capacity of about 103,00 tons in that month being partially filled with 12,000 tons from Aruba, 12,500 tons from Trinidad and 55,000 tons from the Shell hydrogenation plant at Pernis in the Netherlands.42 This geographical diversity in the relevant sources of supply can be seen as late as August 1940, when the fact that 6.3 million out of a total of 27.8 million tons of oil imports scheduled between May 1940 and April 1941 would originate in the United States could prompt the following observation."

__________________

Il-2Bugtracker: Feature #200: Missing 100 octane subtypes of Bf 109E and Bf 110C http://www.il2bugtracker.com/issues/200 Il-2Bugtracker: Bug #415: Spitfire Mk I, Ia, and Mk II: Stability and Control http://www.il2bugtracker.com/issues/415 Kurfürst - Your resource site on Bf 109 performance! http://kurfurst.org

Last edited by Kurfürst; 06-19-2011 at 12:08 AM. |

|

#10

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

so lets say that RAFFC had 57 operational squadrons during the 1st week of Sept. 57 squadrons into 5700 sorties = 100 sorties week/squadron. Lets assume 15 Blenheim squadrons (5 x RAFFC and 10 X RAFBC) = 1500 sorties at 230 gallons/sortie = 1108 tons of 100 octane. So our 5 Blenheim squadrons flew 500 of RAFFC's sorties leaving 5200 to be flown by Merlin engined fighters @ 75 gallons/sortie = 1254 tons, so total RAFFC and RAFBC 100 octane use = 2362 tons. This is only about 1/2 the total consumption of 100 octane and it accounts for 5200 SE fighter and 1500 hundred twin engined Blenheim sorties. There simply isn't enough 100 octane fuel users left over to consume the ~4400 tons if RAFFC isn't using 100% 100 octane. Quote:

Can you present evidence stating that even one operational RAFFC Merlin engined squadron was using 87 Octane from July to Oct 1940? If I was an RAFFC pilot and my Hurricane/Spitfire was using 87 octane, when the squadron down the road was using 100 octane, you can be sure that I would have mentioned it my memoirs or complained about it while writing up a combat report: "The Ju-88 got away because I couldn't use overboost..." Yet there isn't a single statement anywhere about RAFFC pilots complaining about the lack of 100 octane engines or fuel, during the Battle. |

|

| Thread Tools | |

| Display Modes | |

|

|